By @puffskein

Recently I have been pleased to see a number of articles talking about the problems women face in the “Tech” industry. I have been honored to be surrounded by a group of very smart women whom I know because I was privileged enough to go to a very good university. Then work reminded me of all the subtle biases all professional women face.

I work in an industry that is for some reason not considered to be “tech” industry - even though I’ve jokingly described the company I work for as “trying to be like google but for advertising.” In the vein of STEM is for everyone, we need to broaden what we think of as the Tech industry - and start critically thinking about how we consciously and unconsciously treat women in all professional environments.

I have many male and female friends who are directly working as managers and leads in very technical fields. A few of them have erroneously pointed out to me that I don’t really work in the tech industry, or if you think that’s bad try working at a tech company, or the best, well, yes you code and do math, but you’re hiding in a border field. Women need to stop themselves whenever they feel they may say something to another women that minimizes their experience (this goes for more than just work related stuff - for instance, if a woman tells you about terrible street harassment DO NOT ask what they were wearing, it is irrelevant and rude).

Yes, I write code - usually for statistical purposes - but also sometimes for fun or just because I wanted to solve a problem. And no, that is not what we should be looking at when we consider whether or not a fields is technical or STEM related. It’s great to encourage people to code - but it is not going to solve the gender biases, both blatant and subtle, that women experience on a daily basis in the workplace. And I assure you that women experience the same things in non-STEM fields - having worked in a commercial kitchen, and a professional theatre (yep, both “male dominated” fields).

For years I thought it was just that I was “young” or looked young. But over the last few months I’ve realized it has nothing to do with that. Throughout my career I have been hit-on in unwelcome ways (by both male and female colleagues - to the point at one company where I felt I had no choice but to leave). I have been questioned by clients along the lines of “wow, did you do this all by yourself little girl?” I have had female executives at my own company say to me, “wow, you really know your stuff,” as if they were somehow surprised that another woman could be incredibly knowledgeable and competent. So please don’t think I’m just picking on men.

Many of these behaviors were not intentional or done with malice, and I make an effort to call people on them because they may not even be aware they’re doing it. I’ve even managed to make some colleagues aware of these situations so that maybe when they see them happening to other people they will stand up for what is right. This is still an uphill battle and the people who are aware of it are often left feeling like the weight of the issue rests on their shoulders and that it is their role and responsibility to change it. This I think is why many women who are successful in these fields duck out after a time. It is exhausting.

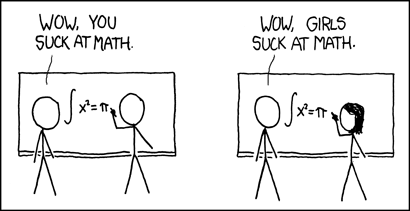

Every time a new “incident” occurs, it eats at you and your self-confidence, and through your shield of righteous indignation. No matter how much you know the person didn’t mean to do it. They didn’t mean to assume your male colleague came up with that idea (even when he said that you came up with it), it’s just a socially ingrained tick. It can leave one feeling a deep sense in futility towards doing good work - why bother if you’re not going to be recognized even when someone tries to make sure you are. Why get advanced degrees in your fields, when you will still be forced to prove yourself to every person you interact with just because you happen to be female? It is also exhausting to call out these issues every time they occur - people assume you’re being a combative b-word (which I actually take as a compliment, but some people do not, and I’ve gotten “performance review” comments along the lines of “too assertive” - which would never be written in a negative way on a male colleagues performance review).

As a society we need to address these subtle biases, not merely by convincing more young women to go into technical fields, but by also convincing more young men to follow their hearts to fields that might be atypical, or not be considered “masculine” enough. It needs to stop being about us “women” vs. them “men” - and stop putting the weight of solving this societal issue on women.